Dylans Story

It is late afternoon at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital and the smile on the handsome face of young Dylan Samuels begins to dim. A nurse has arrived, armed with the latest batch of intravenous antibiotics. Dylan grimaces as she works her way through the syringes. She places a tissue over his palm, soaking up the blood that has come from a thumb prick that is required to check the antibiotics are still the correct dose for him ‘Not very nice,’ he admits, shaking his head.

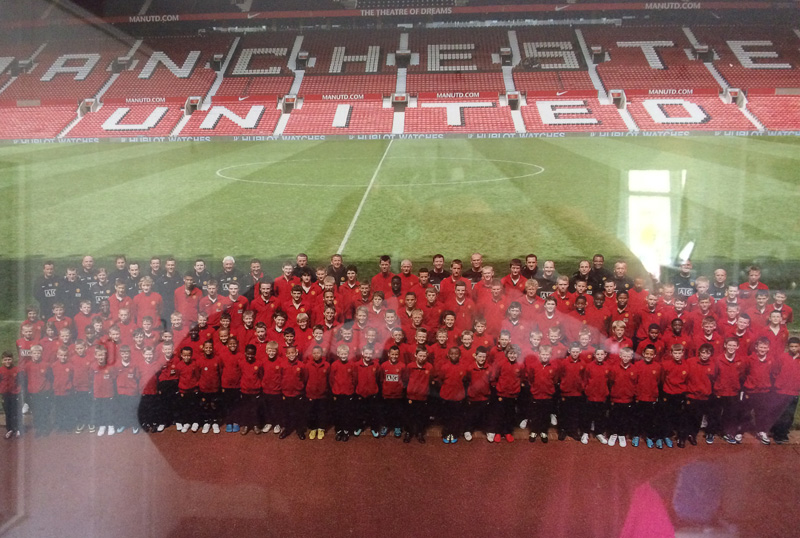

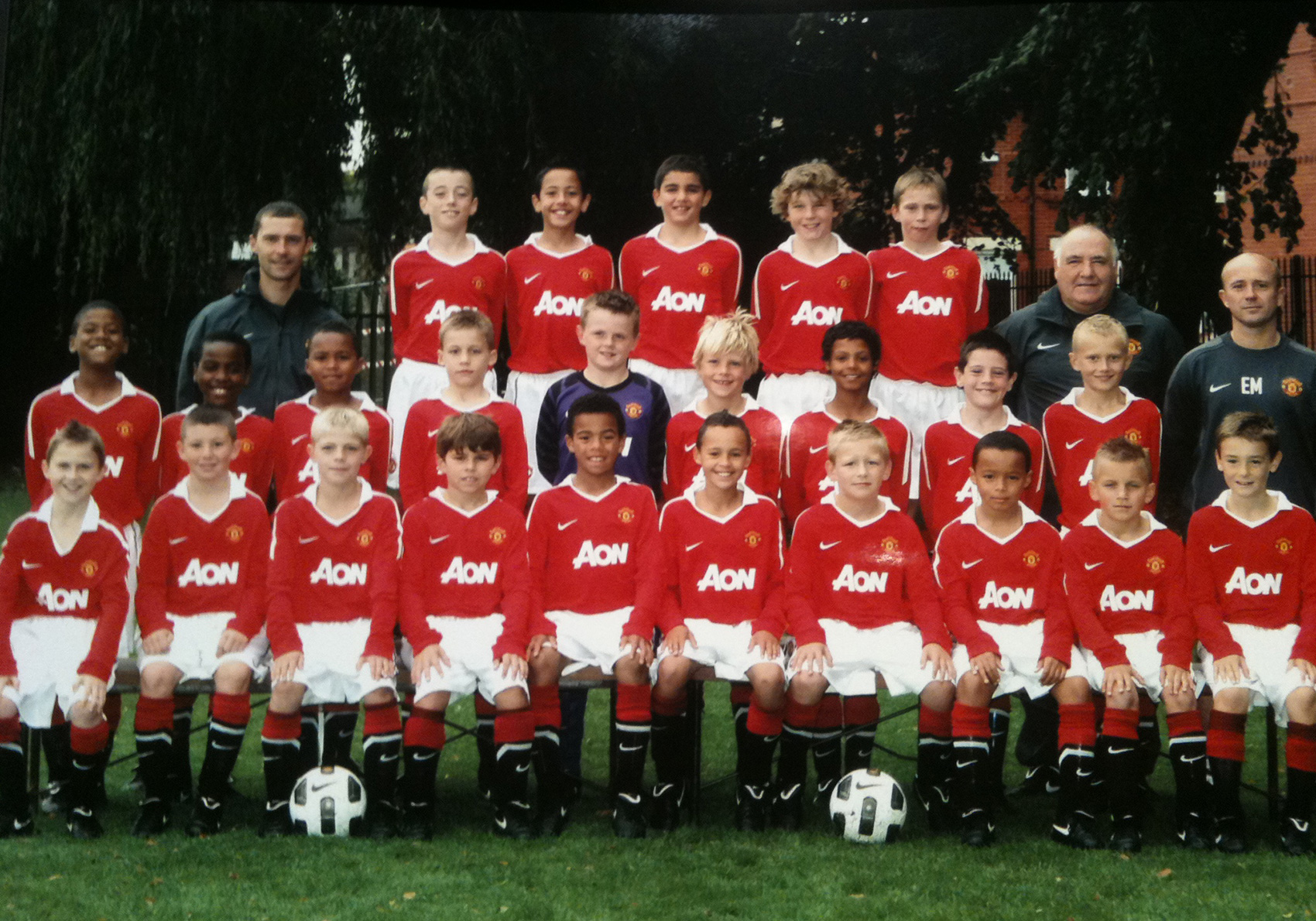

Moments earlier, this charming 14-year-old boy had been reflecting on happier times, on his four years spent as a dynamic central midfielder in the Manchester United academy. Dylan loved every second.

He floods with enthusiasm as he recounts the training sessions at The Cliff and Carrington, the Tuesday evenings he would spend honing his skills under the tutelage of Rene Meulensteen and the occasions when Gary Neville would come along unannounced to coach Dylan and his pals.

‘Just the best,’ Dylan beams,’You can’t put it into words, to play for the club you support. I played in central midfield. I loved watching Paul Scholes, he is my hero. He was only small too. He was just amazing, everything he did. I tried to play like him.’

He casts his mind back to one game against Liverpool: ‘On the Saturday, I was told I was playing. All Saturday and Sunday morning I was focused on it. When you are watching on TV, you are sat there as a fan thinking ‘Come on, get into ‘em!’. Well, this time I could actually do it, do it against Liverpool. I ended up getting taken off before I was sent off!’

Dylan’s dad Stephen grinned. ‘They were two pretty bad, late challenges,’ Dylan admits, letting out a giggle. Perched on his bed and enveloped by his family - parents Steve and Gail and younger sister Natasha - Dylan sighs and glances around his surroundings.

He no longer takes up residence on the lush grass of United’s training ground but a secluded room on Ward 85 of this hospital. It is here that Dylan spent six months last year and has barely been able to go home since the new year.

Dylan goes quiet. He has cystic fibrosis (CF). It is a genetic condition - in Dylan’s case pre-natally diagnosed - where sufferers have thick mucus clogging up their lungs. It makes breathing and digesting food particularly difficult. Around 10,000 people in the UK suffer from CF and only half will live to celebrate their 40th birthday.

Dylan’s story is extraordinary as not only has he battled this illness with fortitude but he also did so while emerging as one of the most sought-after young footballers of his generation in the North West.

He trained with Manchester City, Liverpool and Bolton but he comes from a United family, so United it would be.

‘He was a very good footballer,’ United’s academy co-ordinator Mike Glennie tells Sportsmail. ‘When we take a player on, he fills out a medical form. Of course, the condition stood out. I took advice from the club’s medical team and doctor. Some clubs might have said no. We thought the boy could really play. I have not seen other footballers go as far as he did with the condition. We didn’t take him out of sympathy.

‘He was scouted playing for his local youth club. He then went into a development centre and his quality was so high that we then brought him into The Cliff. He was competing and bettering the highest level of talent in the North West.

‘He had the quality. He had presence, he moved well with intelligence. He was competitive and skilful. He had pace and above all he enjoyed playing football. He played with a smile. He’s a lovely boy, a smashing lad.’

Dylan’s story was - is - inspirational but it has taken a tragic twist. Eighteen months have passed since Dylan last kicked a football.

His dad explains: ‘When Dylan made the step up to full-size pitches, in the Under 12 group, he began to feel a little breathless. ‘He found he was half-a-yard slower than before.’

Dylan had remarkable quality. He had a good presence, he moved well with intelligence. He was competitive, skilful. He had pace and above all he enjoyed playing football. He played with a smile. He’s a lovely, lovely boy and a smashing lad. We only have good memories of Dylan at Manchester United.

He was a very good footballer. When we take a player on, he fills out a medical form. Of course, the condition stood out. I took advice from the club’s medical team and from the club’s doctor. Some clubs might have said no at that point. We thought the boy could really play. I have not seen any evidence of other footballers go that far with the condition. We didn’t take him out of sympathy. We wouldn’t do that. It was right at the time because he had the quality. We knew there might be a point where he began to struggle but at the time it was the right decision. The boy’s dad explained how playing at that intensity could keep him fitter for longer and it became a moral question for us. We took him on and he stayed as long as he could.

Dylan was scouted playing for his local youth club. We have a tiered system where he would then go into a development centre and his quality was so high that we then brought him into The Cliff. He was competing and bettering the highest level of talent in the North West.

Mike Glennie - Manchester United

In July 2011, an annual health review showed Dylan had contracted an NTM (nontuberculous mycobacterial) infection called Abscessus.

‘Normal people can get that and deal with it easily with antibiotics,’ Dylan says. ‘Because of the cystic fibrosis, my lungs struggle to fight it.’

Over the past two years, Dylan’s health has gradually but seriously declined. The infection has damaged and scarred the upper part of his right lung. Barely a day passes when Dylan is not sick. His weight has dropped to only five-and-a-half stone, requiring him to pump high-calorie food into his stomach through a feeding tube.

His cystic fibrosis is particularly acute as he inherited different strains of the disease from both of his parents. His mum passed down the Delta F508 gene, which affects 90% of CF sufferers in Britain. Dylan also inherited from his dad a particularly rare ‘Class One’ mutation - the W1282X gene. This affects less than 1% of CF sufferers in the UK. There is, as it stands, no cure for Dylan’s condition.

All efforts are being placed into controlling the NTM infection but it is not proving easy.

Dylan’s lung capacity has deteriorated drastically. ‘It was at 109% when he was at his best at United and it’s kept dropping,’ Gail says. ‘On one recent reading, it was as low as 32%.’

Dylan is stuck in a cycle of treatments, medication and setbacks as his consultants strive to find a combination of drugs that work.

Gail says: ‘The routine is to try the combinations for 3 weeks, then you stop for 3 months to see how it works but he doesn’t manage to make it through that period.

‘The NTM symptoms return: the fevers, the loss of appetite, the coughing, the sickness. He then comes back in and starts the IV’s again. We just have to persevere. We’re trying to battle the weight but these drugs are terrible for making you sick.

‘He takes the same anti-sickness tablets as chemotherapy patients. Every time we think he might just be getting stronger, every time we think he might be getting back to himself, it wipes him out again.’

Dylan’s condition is worsening. That he is still here today is thanks only to a brutal drug regime. He takes up to 50 tablets a day, in addition to the daily physio sessions and the high-calorie food supplements that are administered via his gastrostomy while he sleeps.

For a boy so active just two years ago, it has been an ordeal. At school, Dylan has always been a bright pupil. His parents were proud when he earned a place at Manchester Grammar School. He left a year ago to attend a school closer to home, after becoming too poorly to make the most of the experience.

His former head of year, Lydia Nelson, recalls Dylan ‘as simply one of the bravest, most gracious, inspiring, hardworking, committed, determined and brave young men I have ever had the pleasure of knowing.’

For Dylan, it has been hard to take. Although he rarely complains, he admits that on the inside, he becomes angry. ‘Yeah, you do. You ask yourself “Why me?”. But you have to fight. You don’t give in. I learned that at United.

‘I was a fit boy at United. Now I couldn’t walk from this bed to the car outside without having a coughing fit and needing a sick bowl.

‘I love sports and I can’t do any of them. Squash, golf, paddle tennis, normal tennis with dad. I love them all. It’s frustrating.’

As for football? Dylan turns his head away, his eyes moistening. ‘He’s a long way away from that,’ Gail admits.

They have recently started a new combination of drugs and Dylan tries, admirably, to remain upbeat.

He has some targets in mind. ‘I try to give myself things to look forward to. I want to go into school again and see my friends. I don’t like them coming in here, they shouldn’t see me like this.’

There are options available for Dylan. Yesterday (Wednesday March 4), the family were given fresh hope when The Cystic Fibrosis Trust announced £20,000 funding for a 10-month stem cell research project that could correct the mutation in Dylan’s W1282X gene. There may yet be a happy ending.

‘We finally have some light,’ Gail said.

The family are praying there will be a breakthrough cure but all options will be considered. Should Dylan’s lung function continue to drop, a lung transplant could be one. Cystic fibrosis patients are seriously considered for transplants when their lung capacity drops below 30%. As it stands, Dylan’s lung function is in the early thirties, leaving him in the cruellest juncture where he is suffering terribly but not quite badly enough to qualify for a transplant.

In the next five weeks, he will be referred to Great Ormond Street for an assessment.

Gail says: ‘It will be four days down there and they will see whether his quality of life is compromised enough to qualify for a lung transplant. A transplant would not cure him but it could strengthen him.

‘We know there is always someone in a worse situation. But if he can’t walk to the car, if he can’t run around, if he can’t go out with his friends, if he can’t do the things a child should be able to do....’. Her voice tails out.

Dylan’s consultants and nurses could not be any more gentle but in the darker moments, there are times when it is hard to keep the faith.

The days where Dylan is sick walking from his bed to the toilet. The days where he coughs so hard that blood spurts out. The days where he is so weak, so fragile that his dad has to carry him up the stairs in their Manchester home.

‘He doesn’t complain,’ Steve says, ‘But he is a little boy. There are times he has said to me “Dad, they are meant to be making me better but I am only getting worse”. As a parent, as the person that’s meant to protect him, it’s heartbreaking.’

In the hospital, CF patients do not mix, due to fears of cross-contamination with infections. I ask if it can become a lonely existence.

‘It can but my mum and dad are always here.’

Steve lies with Dylan every night in hospital, beside the wires and tubes. Amid all the pain, all the suffering, there is something heartwarming about their relationship.

‘I’ve taught him chinese poker,’ Steve grins, ‘We have our box of 1ps and 2ps and we play at night. Backgammon, too. We watch box-sets together. We’ve just finished Breaking Bad. In his last admission, we did Lost.'

They smile at one another and the room falls silent. The conversation moves on and we broach the issue of life expectancy.

‘We know families whose children died as a teenager and we know people who lived into their fifties,’ Steve says, ‘We don’t hide anything from Dyl but we prefer to look up.’

I ask how Steve and Gail focus on their everyday life. Steve manages his own promotional merchandise company.

‘I do two hours in the gym every morning. I am up at 5am to change Dylan’s feed and then I go to the gym at 5.30am. You don’t switch off but it clears my mind. I go out running and have a big cry. That’s my way of dealing with it. Gail has daytimes with him, she sits with him through it all. She finds it a hell of a lot more difficult.

‘But it’s Dyl who has to sleep in hospital, live with tubes inside him, take the IV’s. I stay every night but that’s easy. That’s what you do as a parent. In the last 6 months, there’s barely been a day when he hasn’t been sick. You just want to be here if he needs you.’

This remarkable family have a strong network of family and friends. It’s worth remembering, amidst all the headlines this sport creates, there are some wonderful people in football, too. When Dylan’s former coaches at United learned of the deterioration in his condition, they invited his dad down to The Cliff. Seven coaches sat down with Steve over a cup of tea reflecting on his boy with the bright smile and infectious enthusiasm for the game.

A foundation is to be established in Dylan’s name and is likely to be launched with a fundraising dinner later this year. ‘There’s Something About Dylan’ will encourage donations to the Cystic Fibrosis Trust, the charity for which Steve has already raised close to £30,000 for the Trust, through a London to Paris bike-ride, a three-peak challenge and two Tough Mudders.

‘Don’t forget the abseil down Old Trafford, too.’ Dylan giggles, ‘You were so scared for that!’

‘You were whining at the top! I don’t wanna do it!’ he giggles, putting on his best impression of a crying baby. Laughter breaks out across the room.

‘I’ll keep battling.’ Dylan says. ‘I’m not silly. I know I won’t play for United again. But if I could just chase a ball, score a goal, feel that buzz again, well, that would just be the best.’